Climate resilient gardens

/Revered British gardener Beth Chatto (1923 – 2018) was a pioneering voice in the concept of “right plant, right place”. An approach that urges gardeners to avoid forcing plants into an environment, climate and position they don’t like, to instead take stock of the site and actively select specimens that will thrive there. She demonstrated this by transforming a former carpark made up of gravelly, dry soil and lower waterlogged areas into thriving gardens, full of plants naturally adapted to cope with these conditions. Her book The Dry Garden is still readily reached for by gardeners across the world.

Here in New Zealand, I have explored many diverse dry gardens, inhaling their aesthetic and finding myself intrigued by each gardener’s planting and approach. These are gardens that have a spare elegance, a new beauty that feels slow and calm.

Most recently I visited two extraordinary gardens in Cromwell, a place renowned for its stony ground, painfully hot and dry summers and equally, painfully freezing winters. With lots of water, and maximum composting, it would be possible to plant a traditional ornamental garden here, however, as I found out, there are equally attractive alternatives to be considered.

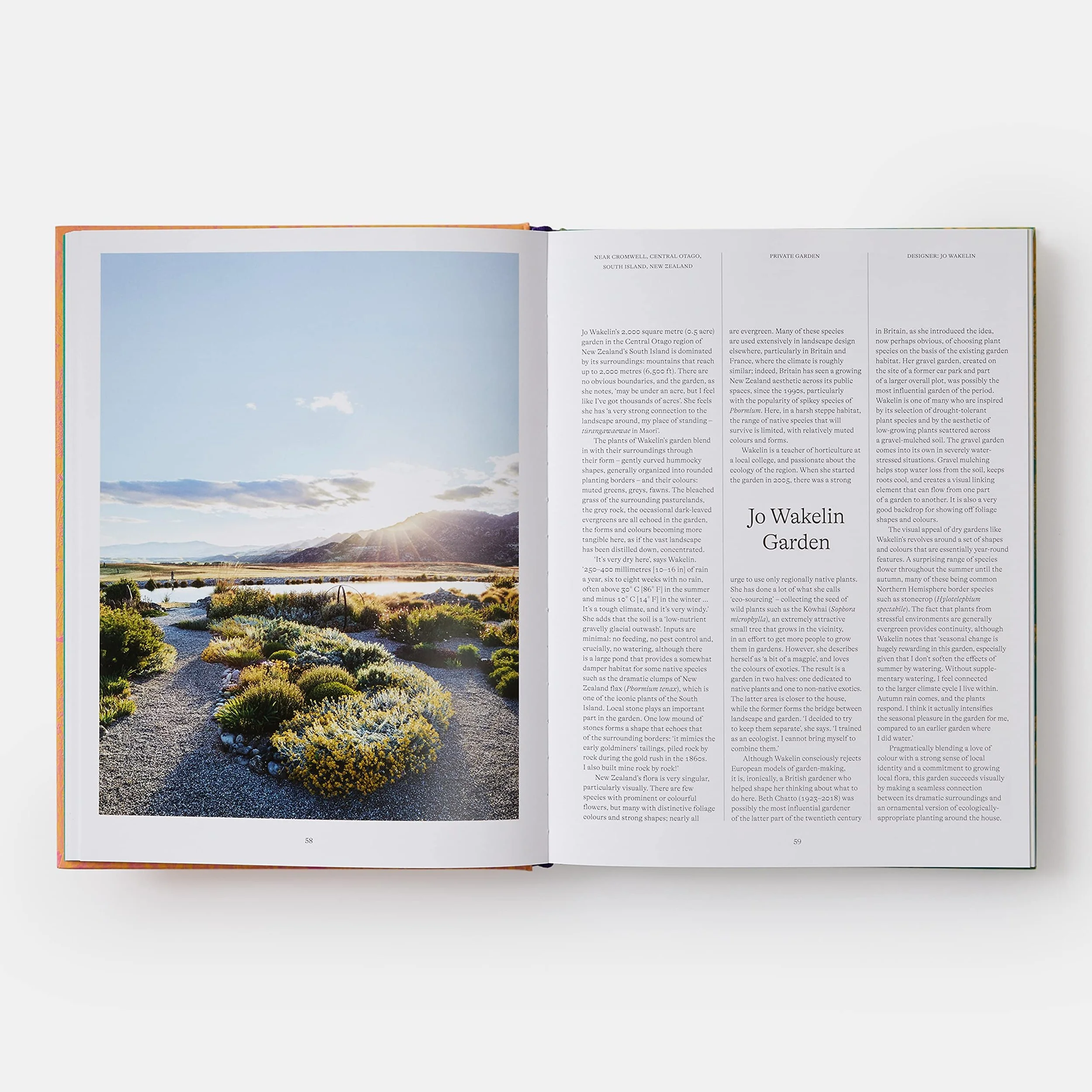

Jo Wakelin’s garden featuring recently in WILD The Naturalistic Garden by Noel Kingsbury and photographs by Claire Takacs.

Top horticulturist Jo Wakelin chose to create a garden for herself, never with the intention of opening to the public, but as a personal pathway through some tougher times. Since then, her resulting work has received international acclaim for its sustainable approach and seasonal display.

As a garden that receives zero watering support, Jo has applied a thick layer of gravel as protective mulch. Much of her garden is made of hardy plants, that hump and mound around each other in reflection of the dramatic borrowed landscape.

“ My landscape was created to fit as subtly as possible into the awe-inspiring surrounds and a harsh dry climate.

I wanted to incorporate strong design with plants that could thrive without any watering where the annual rainfall can be as low as 280 mm.

For me, it is also an expression of a range of emotions. I feel the shakkei principle tied the garden to its surroundings which I find so beautiful.”

Jo Wakelin’s garden in spring.

Jo Wakelin’s garden in mid autumn.

In contrast, is Karen Rhind’s garden down the road. Here I fell in love with her tall border of grasses, mixed with tough perennials, which receives a little additional watering on top of natural rainfall. Her use is still far below traditional watering practices.

Both gardens don’t look or feel familiar in comparison to most New Zealand gardens but do reflect a style and attitude of planting that has gained great traction in other parts of the world, particularly those that share similar climates such as parts of Spain.

Karen Rhind’s grass and perennial border, shown here in mid autumn. This receives minimal additional watering support.

Gardener Jenny Cooper of The Blue House, learned the lessons of considering her site the hard way.

Moving to dry and windy Amberley, North Canterbury she created her garden from scratch, using common practices learned over many years. But over 5 years, despair set in as she watched her heavily composted beds whip up and away in the howling nor’wester. Stressed plants withered in the dry heat and she grew tired of racing around with a hose as much as staking waterlogged plants when rain did arrive.

After much research, she formed a new strategy for planting resilient beds suited to her area and is well on her way to her goal of having half of her large garden exist water-free, with no rain, for 6 weeks to three months in summer. What’s more, these dry beds are tough, remaining undamaged from screaming winds and having no fungal disease.

Dry beds at The Blue House

Colourful and vibrant planting at The Blue House that receives no additional watering support.

I queried Jenny on some of her most important techniques for those looking to start a resilient garden, all of which she shared with enthusiasm.

For new beds, don’t dig

When creating new beds in lawn or ungardened ground, cover the area with cardboard to kill the grass and mulch heavily to a depth of 12+ cm to completely block out the light. Leave fallow for a few months if possible. When planting, move the mulch back, plant at soil height and replace the mulch around your tiny specimen. She readily plants directly into the lawn soil with no turning over or cultivating.

Plant Small

Skip the $150 trees and buy the $30 whips! By using young plants, you harness their youthful vigour. Their early growth spurt needs to happen in your soil, not the pot so that they form the best root system they are capable of. Ideally, when planting in autumn and winter, plant with bare roots. Shake off potting mix (which dries and wets at different rates to native soil), cut off girdling roots and spread the rest. Small plants cope best with bare rooting, this is called “slow gardening” after all.

Grow the soil

Jenny has a strong focus on mulch and adds no other soil amendments, even to the hole created to pop in a plant. Young plants will initially live on the dead roots of grass which also makes for excellent, humus-rich soil.

Intact healthy soil contains mycorrhizal fungi which form symbiotic relationships with most plants, bringing them water and nutrients in exchange for carbon. Once a plant has mycorrhizal input, it is much more resilient to drought.

Avoid bare soil at all costs

As Jenny points out, in nature, bare soil never really occurs, with Mother Nature quickly covering in weeds. Her preferred mulch is ramial woodchip (made from a whole living tree mulched up, leaves and all) while staying away from bark, which inhibits decay and fungal growth. While woodchip encourages the mycorrhizal fungi, she also uses river stones, pine needles, grass clippings - anything to cover the soil. These mulches keep the moisture in and stop the weeds. Weeding is no longer something that is an issue in her garden.

Plant in zones

The hardest thing Jenny learned was to strictly plant in zones. In a dry bed, one drooping plant is enough to make her put on the hose so, to remedy this, each year she is on the lookout for plants in the wrong place, either shifting or giving away. Putting the hose on dry-loving plants such as salvias, lavender and sedum, makes them soft, floppy and disease prone.

This is an expanded version of the article featured in my Stuff ‘Homed’ gardening column for beginners , The Press, Dominion Post and other regional papers on June 23rd 2022

All words and images are my own, unless noted.